IATEFL Failure Fest: how is failure a better teacher than success?

When I first heard that Ken Wilson was going to lead a session on failure at IATEFL Liverpool, I was intrigued, but mostly I was grateful. I imagined the Failure Fest as a space for reality checks, healing, and great learning for ELT professionals. Sophia Khan wrote about this beautifully in her debut blog post, Why We Should Celebrate Failure Fest,

what I like about Failure Fest is that it says: “I am human, just like you”. It focuses on our similarities rather than our differences. Finding a shared emotional experience creates a sense of solidarity, mutuality and possibility. Because we are alike – human – I can learn from your mistakes – and your achievements – as if they were my own. What is possible for you is also possible for me. No matter how qualified or experienced you are, we are more alike than different. Think about it: have you ever had a worry, feelings of self-doubt, anxiety about what the right thing to do is – then you find that someone has gone through, or is going through, the same thing as you? It is such a blessed, wonderful relief to know that you are not alone, even if you still don’t have all the answers.

And this sense of relief is what we all felt during the fest. The relief was expressed through having a bit of fun (Caroline Moore‘s punctual cow bell and Ken’s witty introductions), and through the presenters’ ability to show their vulnerability.

What struck me about each of these engaging storytellers (Ken Wilson, Bethany Cagnol, Chia Suan Chong, Andy Cowle, Herbert Puchta, Jeremy Harmer, Rakesh Bhanot, Valeria Franca, Willy Cardoso) was the fact that they were all able to laugh at their failures. However, among the laughter, each presenter also expressed a sense of discomfort that came along with the initial moment of failure — or as Kathryn Schulz described during her TED Talk, On Being Wrong, how it feels to realize that moment of failure. Jeremy Harmer embarrassingly admitted that the first thing he had ever taught a student was to describe his “big, red, bushy beard.” Chia Suan Chong talked about how she cried after the miscommunication with a German bus driver. Valeria Franca described the dread of seeing little Luciana come up to her after her revamped English lesson on clothing. Bethany Cagnol shared the devastation she felt after being fired for having fun with her students.

“embracing our fallibility”

For many of us, the laughter doesn’t usually come immediately after these moments. It may come years after and for some people it may never come. There is something safe about hiding in the belief that we shouldn’t make mistakes:

“We get sucked into perfection for one very simple reason: We believe perfection will protect us. Perfectionism is the belief that if we live perfect, look perfect, and act perfect, we can minimize or avoid the pain of blame, judgment, and shame.” – Brené Brown

I think one of my biggest failures has been holding on to this idea of perfection. I used to work late hours planning the “perfect” lesson, and on a few occasions I even broke down crying after class, realizing I had answered a question “wrong”. “I’m a trainer dammit! I *should know these things!” Although I may not be in a space where I can laugh at this failure, I feel a great sense of lightness at being able to admit it. And I know I am able to express this thanks the Failure Fest and also thanks to what teachers have been writing about failure over the past few weeks (Kevin Stein, As many flavors of failure…; Chris Wilson, Failing at Modal verbs).

The Journey of Failure

An old post of mine, The Teacher as the Archetypal Student, came to my attention the night of the Failure Fest when a new reader left a comment. I hadn’t read this post in years (written on September 11, 2010). Although my post doesn’t directly express my concern about failing, this reader saw it clearly:

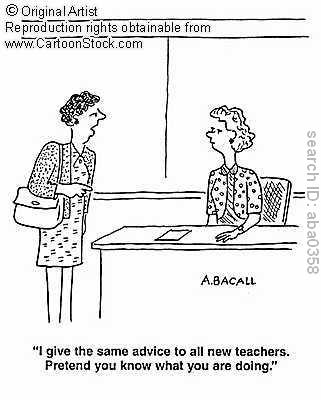

I think it is the responsibility of the teacher to show her students that it is okay to make mistakes. Students can learn more from a teacher who allows herself to be vulnerable in front of her students, rather than an obviously flawed person who pretends to be perfect. Students will respect a teacher who openly admits her faults or knowledge gaps. When a teacher does this, learning can become a journey that the teacher and student go on together.

And so I thank Ken Wilson and Caroline Moore for providing a space to the world of ELT to embark on this journey of seeing the light between the cracks of failure. I also have great gratitude for all the presenters for sharing their light.

Willy Cardoso left us a wonderful quote to keep us pondering along this journey of embracing failure:

It is this great struggle, to choose between having a lot of freedom and having a lot of stability that makes us people. (…) And when you believe you can achieve both, it’s probably the beginning of a failure story…which is inevitable. You have to choose one when you know you won’t have much of the other. (…) I’m not likely to go about cycling on busy roads ever again because I don’t want to run the risk of falling, although I know it would give me a great sense of freedom. So in this regard I choose stability over freedom. In love, on the other hand, I will always be willing to fall.

In teaching and in learning, what is this love you are willing to fall for?